*there are a few but not many spoilers…

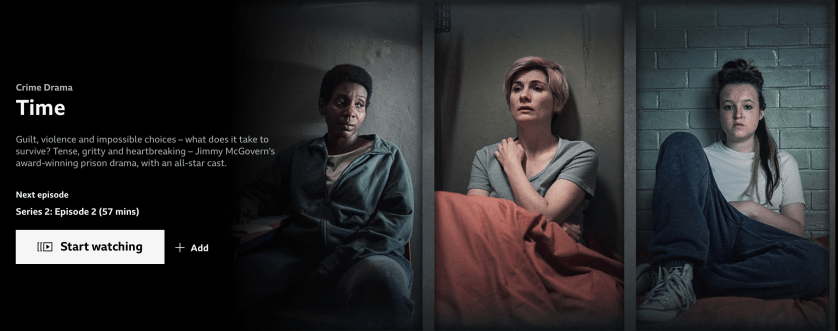

The second season of Jimmy McGovern’s prison drama ‘Time’ has just been released on the BBC. The focus of this season is women in prison, and from the opening scene it becomes apparent that the past, present and future motherhood of the characters is the lens through which we are going to view their experiences of imprisonment. As a researcher whose focus for the past ten years has been the sentencing of mothers, I was excited by this and curious to see how McGovern represents or fictionalises their experiences. I’ve read a few reviews of the season, and found it interesting that one reviewer saw the focus on motherhood as both the biggest strength and weakness of the series, wishing that the drama would show the women as more than mothers. The reviewer noted the women are ‘driven and reduced by it [motherhood]’. She’s absolutely right in that. Motherhood and punishment have a complicated and reductive relationship. A woman’s motherhood is often the most punished part of her when she is sent to prison – I’m writing a book about that – but it’s also disregarded, as Time demonstrates.

We meet Orla, single mum of three, sending her children off to school without telling anyone she’s going to court to be sentenced for ‘fiddling the ‘leccy’. Apparently, whoever was advising Orla had told her that she’d not go to prison, but we see her distraught in the second scene as she’s driven from court to prison in a ‘sweat box’. She doesn’t know where she’s going, when she’ll get there, or most importantly, and distressingly, who has collected her children from school. Electricity theft can be punished with anything from a fine through to a five year prison sentence. Orla’s been given six months, meaning she’s facing a three month stay in prison.

What we see happening to Orla is the experience of many mothers who are sent to prison for short sentences. So if you watched it thinking it was a little far-fetched – not knowing where her children are, the inability to make arrangements for them because all her numbers were on her phone (which has been removed from her and won’t be returned until she leaves prison), the seeming lack of concern for three children aged 7, 9 and 13 who have been left without a parent, her mother taking on the care of them even though Orla knows her mother’s alcoholism makes her an unsuitable carer, their subsequent removal into foster care, the fact that Orla isn’t notified of that despite two letters being sent to her at the prison, the children’s distress at a visit, and Orla leaving prison 3 months after arrival without the house, job, and family that she had before she went in – I’m sorry to tell you that it’s not at all unrealistic.

The Deputy Governor comes to see her when she tries to get someone to listen to her distress about her children’s removal into foster care. He apologises for the fact understaffing in the prison meant that the letters social services sent to her weren’t given to her, and then he says,

‘You’ll just need to get a job, save some money, rent a place, and get them back.’

I’m guessing the writers intend this to be a set up for future episodes where we will see some of the flaws in the DG’s seemingly very clear plan for family re-integration post-imprisonment. Of course, the real question is whether punishment is supposed to include losing your house, job and children…

Sentencing was also referenced in the discussions about the sentencing of pregnant women. Kelsey, a young heroin addict, is on remand (in prison before trial) and discovers when her urine is tested on arrival, that she is pregnant. Her initial plan to have an abortion is affected when Abi, the third new arrival, tells her,

‘Judges don’t like giving long sentences to pregnant women. He’ll go easier on you if you’re pregnant.’

Kelsey’s subsequent decision to keep the baby in order to get a lesser sentence, is of course what many people believe happens, and that’s why we often hear people saying pregnancy shouldn’t be a ‘get out of jail free’ card. There’s an assumption that women are manipulating the system – I hear it from judges as well as it being an opinion that is expressed if you read the comments below any media article on the topic.

Pregnancy should be a consideration when sentencing a woman. In fact the Sentencing Council are currently conducting a consultation on a sentencing guideline addressing the situation. Pregnant women continue to be sent to prison despite the expert view of the Royal College of Midwives, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, NHS England, and the Prison Ombudsman, that pregnancy in prison is high risk for a baby, and imprisonment should be avoided where possible. In prison the chance of having a still birth is seven times higher than in the general population. Prisons do not have adequate specialist health care. In the tragic case of Aisha Cleary, whose mum was a teenager on remand, the prison officer silenced her call bell because she was asking for help too often. A teenager was left to give birth alone in her cell and her baby died as a consequence.

Even if the baby is born safely, there is no guarantee of a place on a Mother and Baby Unit, and Kelsey’s confidence that she and her baby would be able to stay together there, is sadly misplaced.

I personally don’t think there’s much truth at all in the idea that women become pregnant or stay pregnant in order to avoid long sentences. The unplanned and uncertain nature of pregnancy, and the long delay in bringing cases to court, mean that women cannot predict when they will be sentenced, let alone time the arrival of a baby to influence sentencing decisions.

I think Jimmy McGovern has got it right focusing on motherhood. Many women in prison have been, are, and will be mothers, and it’s a complex and critical part of their identity which should get our attention.