A week ago I intended to write a third and final blog post about the brilliant BBC drama ‘Time’ by Jimmy McGovern. I was going to write about Orla and her children. About the inadequacy of the provision made for children whose mother is imprisoned. It would have said, no this is not fiction.

Yes, women and men are released from prison with no housing but a tent, or in one family I met, an instruction from the prison to ‘tell your probation officer which bench you usually sleep on and that will count as an address.’ If you asked me to take a guess about the continuation of Orla’s story, I’d say that she and her children would have a very hard road ahead, which may or may not end up with them reuniting as a family. I would have included a link to this film which I made for and with Community Justice Scotland a few years ago, when Ang agreed to be interviewed by me about the experiences she and her two boys had when she was sent to prison. I’d have said that your horror and upset at the suffering of Orla and her family in Time is entirely appropriate and that by the time my interview with Ang ended, everyone in the room, including the camera man, was weeping.

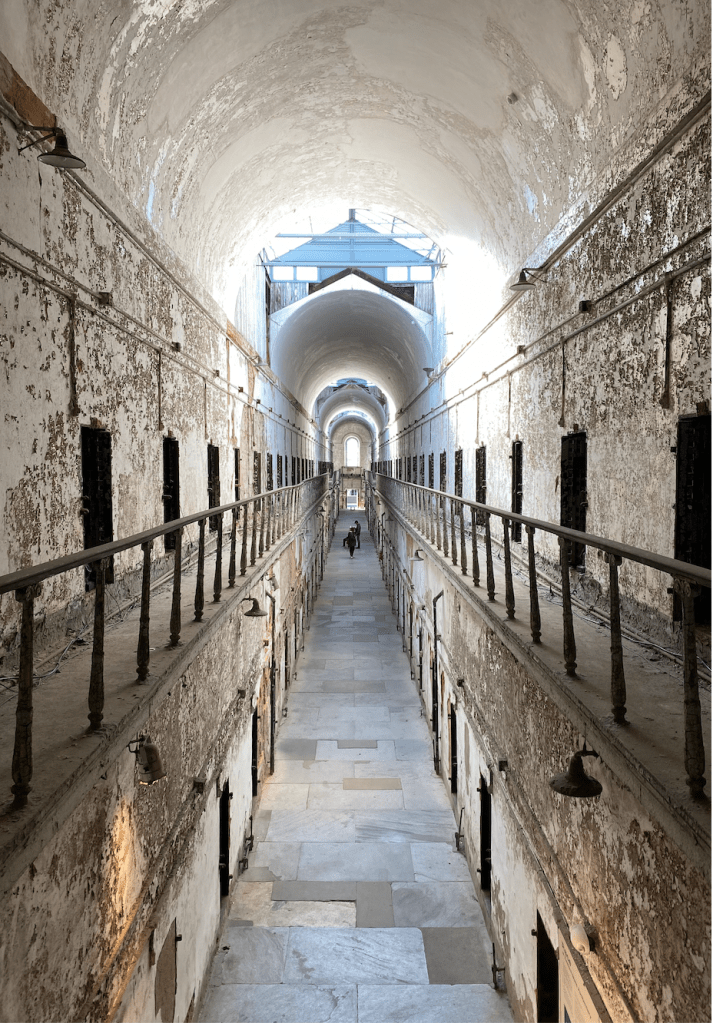

I didn’t write the blog because I ran out of time before I travelled to Philadelphia to attend the American Society of Criminology Annual Conference. It’s a huge academic meeting: 4000 criminologists, 4 days, more than 700 presentations, held in a country which has the highest rates of imprisonment globally. The day before the conference began, I visited Eastern State Penitentiary which was operational from 1829-1971. It’s one of the most famous prisons in the US. The penitentiary refined the system of ‘separate incarceration’ founded on the belief that a person who had committed a crime would find redemption and rehabilitation from the good within themselves, if left to discover it. Unless of course they first experienced the madness brought about by solitary confinement. The separate system was abandoned due to overcrowding. An early example of penal change driven by operational rather than justice-based motivations. The prison now provides a space for us to see the realities of imprisonment and its history, using art installations and digital media exhibitions to educate about mass incarceration in the US and the particular and extreme harms of imprisonment on individuals, families, and societies.

You probably already know that in the US the intertwining of racism and punishment has led to the mass incarceration of particular groups of citizens, and a mindset and laws which have resulted in an increase in the number of people incarcerated in jails and prisons, even whilst criminal offending reduces.

Poverty is punished. Blackness is punished. Mental illness is punished.

At the conference I spent time in discussions about courts which do things differently. Courts which put services and support in place for people who’ve committed offences, so that they don’t leave court or prison to sleep on a bench, or return to a violent relationship, or have another child removed by the state because they can’t seem to provide housing and security for that child. Amanda, who had been incarcerated several times for offences linked to addiction, losing two children into state care in the process, was finally offered help instead of punishment when pregnant with her third child. When asked what she would suggest could be done, the answer was very straightforward: ‘Spend money on the solutions not the problem’. In other words, don’t spend the money locking someone up, use the money to help people address the problems in their lives. Someone else said ‘we spend so much money doing things which we know cause harm and don’t work [imprisonment] so how much of a risk is it really to try different approaches instead? They aren’t likely to be any worse than the things we’re already doing, and there’s always a chance that they may be better.’

And I came back to the UK thinking about the numbers. The fact that we haven’t yet reached the out of control spiralling increases of the US prison population, and how there might still be time to do things differently.

In the state of Pennsylvania where the conference was held, there is a population of 13 million and 73,000 people are incarcerated at any one time, and 170,000 people are incarcerated every year. 1 in every 4 people in the United States has experienced incarceration. That means that 1 in every 4 people has, in the pursuit of an idea of ‘justice’, experienced time in an underfunded, sometimes brutal, always dehumanising-to-some-degree, system. Then, when they’ve reached the end of their time inside, they are sent back into society without the means to re-integrate, find a job, a home, build a life.

We have a population of around 60 million in England and Wales, and last week, a prison population of 87,744. It is predicted that our prison population will rise over the next five years (and one assumes forever after if nothing is done to change that trajectory).

That doesn’t seem like a great way to build a safer, better society.

There were 3,595 women in prison in England last week and as I came back to write about Orla and Kelsey and Abby I reflected on the fact that Jimmy McGovern’s writing team have done a great job in putting out there the often confused, painful and pointless realities of punishment through imprisonment and making us ask the questions (and care about the answers): did Orla ever get her children back? Is the just punishment for ‘fiddling the ‘leccy’ to lose your children, your home and your job? Is it right that punishment knocks over a life in a way which will never allow you to right it again?

Time is fictionalised but not fiction.

I have hope that if we use our collective imagination we can tell better stories…